Introduction to English Traditional Tunes

Contents

Introduction

By and large English folk tunes are functional: they were played for dancing or used for the melody of songs, and so their history reflects the history of song and dance (e.g. as a consequence of the absorption of new dances such as the waltz and the polka into the tradition, the associated tunes became part of traditional players’ repertoire). This guide will serve as an introduction to tunes in their various functions and briefly examine the players, the instruments, and how you can search for tunes.

Dance tunes

Social dance tunes

The earliest records of traditional tunes are often in books giving dance instructions. Preeminent among these is Playford’s The English Dancing Master, first published in 1651. This work went through a large number of editions over the next three quarters of a century with the title soon being shortened to just The Dancing Master. Tunes such as “Constant Billy” which became a staple in the traditional musician’s repertoire, particularly for morris dance, were published here. However, we know that the Dancing Master drew on already existing tunes and dances for its content, e.g. the tune “Sellenger’s Round” was extant in 1598, and was published in the 3rd edition of Playford in 1657. The VWML possesses a number of editions of the Dancing Master and many later books of a similar sort published by Thompson, Rutherford, Preston, etc.

From the second half of the eighteenth century many amateur and semi-professional musicians wrote their own manuscript tune books, into which they copied tunes from printed or oral sources. Sometimes musicians would play for dancing in the evening and then as a west gallery musician at church, so some of these tune books contain a combination of secular and religious music.

A number of printed and manuscript tune books can be found in the collections of early folk collectors, such as Frank Kidson and Annie Gilchrist, which they used to aid their research into song and tune histories. They, along with other collectors of the time, were also active in collecting dance tunes still being played by traditional musicians, such as John Locke.

Morris and sword dance tunes

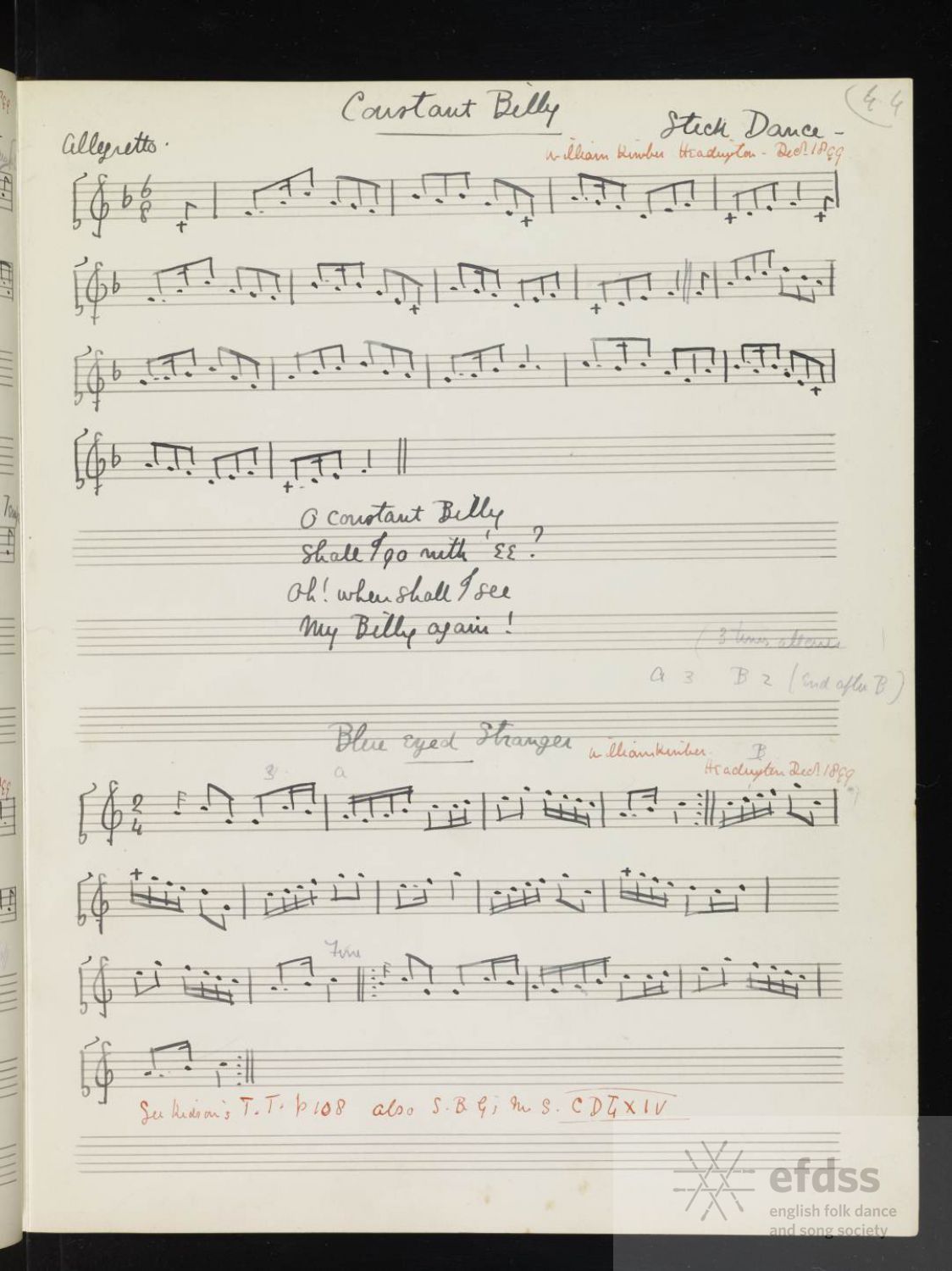

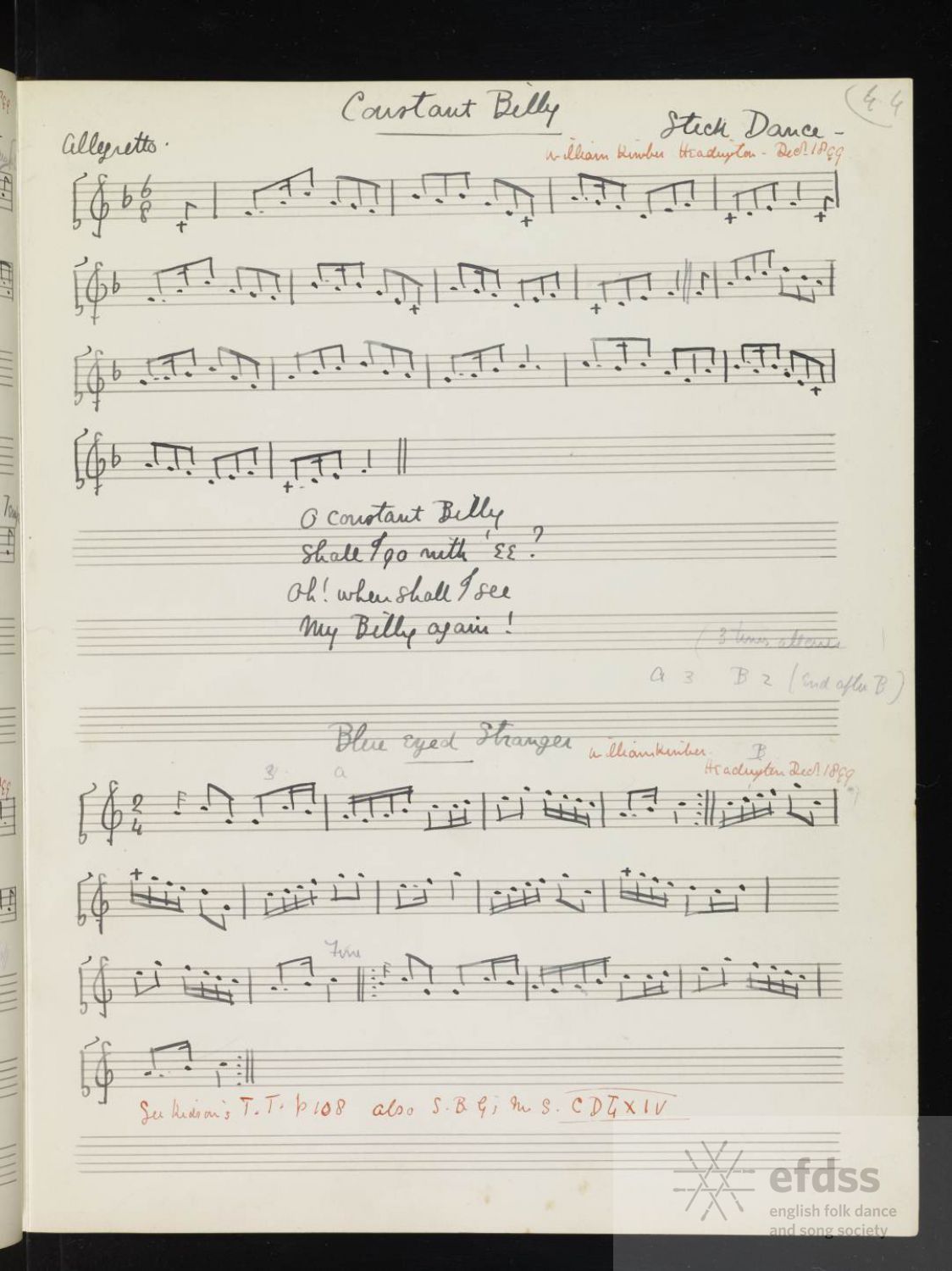

The tunes which were played for morris or sword dancing could have originated from a variety of sources, e.g. country dance tunes or song tunes, but later became part of the display dance tradition. The first major collector of morris and sword dance tunes was Cecil Sharp. Sharp first saw morris dancing on Boxing Day of 1899 whilst staying at his mother-in-law’s house in Oxfordshire. The side was Headington Quarry, and the musician was William Kimber, an anglo-concertina player. Cecil Sharp noted half a dozen tunes from Kimber on that occasion, such as Blue Eyed Stranger.

Cecil Sharp's transcription of 'Blue Eyed Stranger', from the playing of William Kimber

Later, Sharp became interested in other forms of display dance – particularly long-sword and rapper as found in the North-East of England, and so examples of their tunes can also be found in Sharp’s collection. It is interesting to note that the tunes for Rapper dancing standardised to jigs in the 19th century. This tune type is perfect for the prescribed shuffle stepping which continues throughout the dance. A number of tunes used for traditional rapper dance can be found in the pages of the 1874 publication Kerr’s Musical Melodies (Heaton, 2012. Rapper : the miners’ sword dance of North East England. EFDSS).

Lionel Bacon compiled all the collected traditional morris tunes from the early 20th century together for his Handbook of morris dances published in 1974, and remains one of the most comprehensive sources for traditional morris dance tunes.

Instruments

The fiddle is probably the most important instrument in English folk dance music, though the pipe and tabor remained the instrument for morris dancing until the early nineteenth century. In the later part of the nineteenth century free reed instruments (concertinas, melodeons and other button accordions and mouth organs) gained popularity. In village and church bands flutes, clarinets and serpents were common, possibly in the hands of musicians who had learnt in military bands.

Bagpipes were once a common instrument in England, and there have been many attempts to revive them. The Northumbrian small-pipes constitute a continuing living tradition with a distinctive repertoire.

Nowadays, revival folk performers may play almost any instrument. The Library has many tune books produced for specific instruments and tutors for the instruments most commonly played in the folk music today.

Song tunes

Song tunes are usually considered in relation to a particular song text (i.e. one text to one tune), but historically the relationship was not so straightforward. For folk songs, a single song may have been collected with a variety of different tunes, and a single tune may be used for many different songs. This is not surprising – prior to the 19th century when many songs were printed on broadside ballads and sold on the streets, they would sometimes indicate the tune to which they should be sung. It was important, therefore, that this tune was already familiar to the general public and so popular songs were used again and again.

Sandyford Sensation, with tunes specified

Whilst the 19th century ballad scholars such as Francis James Child were interested in songs from a literary perspective, many of the early 20th century song collectors, such as Ralph Vaughan Williams, tended to focus on the song’s tune rather than words. This is because they considered the tunes to be more oral in nature, open to change and variation, and therefore more strongly associated with the folk tradition. Some of the collectors also suggested that many folk tunes were modal (of the church modes) which they linked to historic music. The modes and tune collecting is explored in the two chapters by Julia Bishop in Steve Roud’s (2017) Folksong in England.

Reasearching tunes

Many tunes have changed their names over time, or go under multiple titles, so this can make tune research difficult. The VWML has created a Dance & Tune Index to help researchers locate dance tunes in the various books, pamphlets and records which we hold. Users can search for tune by given title, performer name, key, and a whole host of other fields. See “Search and browse tips” for more information on how to search.

Digitised Resources

The VWML Historic Dance and Tune Gallery - digitised copies of a range of historic published and unpublished dance and tune books, including Thompson, Preston, Skillern, etc., and Malchair, Kitty Bridges, etc.

The Village Music Project –contains transcriptions of a large number of historic manuscript tune books held in both public institutions and private hands.

The Dancing Master, 1651-1728 : An Illustrated Compendium By Robert M. Keller – a digital collection and index of the tunes printed in Playford’s Dancing Master.

Books

Dance Tunes

Whilst it’s possible to search for tunes online and using the VWML’s indexes, books can be useful in grouping tunes from certain eras or for particular purposes together. Here is a selection of some of the best books for those interested in exploring English tunes:

Callaghan, B., & Stewart, P., 2007. Hardcore English : a collection of 300 tunes from English manuscript, recorded and aural sources. London : EFDSS.

Kennedy, P., 1950. Fiddler’s tune-book, vol. 1-5. London : EFDSS (Influential tune books of the 1950s)

Bacon, L., 1974. A handbook of morris dances. Bedfordshire: Morris Ring.

Barlow, J., 1985. The complete country dance tunes from Playford's dancing master (1651-ca.1728). London : Faber Music.

Song tunes

Bronson, B.H., 1959. The traditional tunes of the Child ballads : with their texts, according to the extant records of Great Britain and America, vol. 1-4. New Jersey : Princeton University Press. Gathers together all the tunes of the Child ballads as found in manuscript collections of song collectors.

Simpson, C., 1966. The British broadside ballad and its music. New Jersey : Rutgers University Press. Explores the tunes which may have been used for broadside songs.

Davidson, G.H., 1847 and 1848. Davidson's universal melodist : consisting of the music and words of popular, standard, and original songs, etc., vol. 1-2. London : G H Davidson. A useful resource for historic popular song tunes.

Roud, S., 2017. Folk song in England. London : Faber. Julia Bishop’s two chapters on song tunes are essential reading on this subject.

Recordings

Apart from a small number of early phonograph recordings and performers such as William Kimber (Anglo concertina) who made commercial records in the studio, the bulk of recorded music dates from the middle of the twentieth century and onward. A representative selection of field recordings appears on various CDs in the Topic Records Voice of the People series, notably:

Voice of the People, Vol. 9: Rig-A-Jig-Jig - Dance Music of the South of England. London : Topic.

Voice of the People, Vol. 19: Ranting & Reeling - Dance Music of the North of England.

The VWML has both commercially issued records and unpublished field recordings. The British Library Sound Archive is also a major collection of folk and traditional recordings, some of which can be listened to online.